Unions

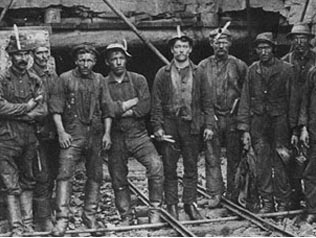

Over the century’s of mining unions have played a major factor in the operations and labour force of the Cape Breton Coal industry. Some of the influential unions were:

Provincial Workman’s Association

The precursor of the United Mine Workers’ Union in Cape Breton was the Provincial Workman’s Association (PWA). With its beginnings in Springhill in 1879, the union was an association that evolved when the men united in an effort to regain an original wage that had been doubly cut. The men walked out and refused to go back to work until their wage was restored. Within a week, it was restored and this successful walkout spurred them on to form the Association.

In 1881, the PWA was incorporated into an act of the Nova Scotia Legislature. In 1881, Robert Drummond toured Cape Breton as an agent of the PSW and it was obvious that the miners working there needed an Association as wages were low, hours were long and Company store prices high. In spite of a hostile attitude towards unions, the miners were becoming more and more enthusiastic and soon four lodges were organized, including Drummond Lodge (Sydney Mines), Equity (Caledonia) and Island and Unity Lodges (Bridgeport). By December 1881, over 50% of the Island’s mines had joined. Shortly after, the number of lodges increased to eight.

People were still afraid to disobey the Company, and so it was often hard to find meeting places. The essential points of the PWA were unity, equity and progress. It wanted to make the mining population a respected segment of the community. The PWA used three notable tactics to accomplish its aims: strikes, lobbying and politics. Strikes were used as a last resort when all else failed. The first period of the PWA (1879-1898) was largely devoted to a reform of the condition under which the miners lived. The second period of the PWA (1898-1917) was devoted to increasing the wages of the miners and improving their standard of living. The PWA was amalgamated in 1917 with the United Mine Workers of Nova Scotia to form the Amalgamated Mine Workers of Nova Scotia. During its term, the PWA made some outstanding contributions to the coal fields of Nova Scotia besides being the first union association to form in Cape Breton.

1. The PWA secured legislation favourable to miners such as the Arbitration Act of 1888 passed by the Liberal Government; 2. Strikes and lockouts were reduced; 3. The PWA won safety improvements in the Coal Mines Regulation Act including the basic safety measures under which the collieries of the Province operated.

The strength of the Association wavered over the years. For instance, in 1904, a strike at the Sydney Steel Plant was so weak that the Company was able to take in replacement workers. In 1909 the arrival from the United States of the United Mine Workers of America resulted in a number of Cape Breton Lodges being dissolved and UMW District 26 being formed.

United Mine Workers of America

District 26 of UMW was formed in Cape Breton in 1909 when a number of the PWA Lodges dissolved. The president of District 26 was Dan McDougall, Vice President, J.B. Moss, Secretary Treasurer, J.B. McLachlan and International Board Member, James D. McLennan.

The UMW had a difficult struggle as the PWA joined forces with the Dominion Coal Company to resist the new union. On July 6, 1909, a strike broke out when attempts to meet with the operators of the Dominion Coal Company proved unsuccessful. During this strike, the UMW members were not working, but those who still followed the PWA remained working. The striking miners received no media support as the struggle progressed, and the Company erected electrified barbed wire fences.

As the months passed by, the men and their families found it harder to survive on handouts and the small relief amount the UMW provided on a weekly basis. Also, the Company had hired strike breakers from Belgium, Montreal, Scotland, Wales, Newfoundland and even some from Cape Breton and housed them in specially built barracks as they feared for their safety. While their supporters were looked upon as radicals, the strikers were condemned in the press and from the pulpit. By November, only 500 men remained on strike and by April 28, 1910, the strike of eight months had ended.

Technically, the strike was a failure. The United Mine Workers had failed to win recognition, it was monetarily defeated. Between 1911 and 1915 membership dropped (reportedly only 30 staunch supporters remained) and its character was taken away by the International. The union was to rise again when the PWA failed in obtaining fair wages for its members. In March 1917, the PWA and the UMW applied for a conciliation board because of difficulties in matters of wages, working conditions and discrimination. The Commission saw the causes of dispute at Glace Bay as being the rivalry between the two unions and unsatisfactory wages.

In 1917, on recommendation of the commission, the two unions joined and formed the Amalgamated Mine Workers of Nova Scotia (AMWNS).

Amalgamated Mine Workers of Nova Scotia

By 1917, the PWA and the United Mine Workers of Nova Scotia united to form the Amalgamated Mine Workers of Nova Scotia. In 1918, after 38 years of service to the miners of Nova Scotia, the remaining lodges of the Provincial Workman’s Association were dissolved.

In the 1920’s, the Dominion Coal Company’s assets were sold and a new company, the British Empire Steel Corporation (Besco), began operations under the leadership of Montreal entrepreneur, Roy M. Wolvin. By 1921 Wolvin announced there would be a 33.3% wage reduction effective as of January 1, 1922.

E.P. Merril, General Manager, wrote to J.B McLachlan (Secretary-Treasurer, District 26) concerning the wage cut: “Business conditions compel us to very reluctantly ask for a reduction in wages.” The UMW quickly sought an injunction against the wage cut, however, Besco subsequently successfully appealed its injunction. The Gillen Commission was set up in 1922 to resolve the problem. The UMW pointed out that the average production per man was three tons, worth approximately 18 dollars of which the men were paid six dollars. Both sides reached a stalemate resulting in an offer of 30% (1/3 less than the original offer). Reduction in wages was entered for consideration.

The Union was not fully agreeable and so on March 14, 1922, a pithead vote was taken and the agreement was defeated by a seven to one ratio. This prompted the executive of the union to hold a slowdown strike. This was a difficult decision for the miners who were already in very poor financial shape and the Company then announced that no credit was to be given to miners until the strike was over. Soon the board warned the miners that the International would not support them. The miners paid no attention and reduced production by one third.

Davis Day

In March of 1925, Cape Breton coal miners were receiving $3.65 in daily wages and had been working part-time for more than three years. They burned company cola to heat company houses illuminated by company electricity. Their families drank company water, were indebted to the company store and were financially destitute. Local clergy spoke of children clothed in flour sacks and dying of starvation from the infamous “four cent meal”. The miners had fought continuously since 1909 for decent working conditions, an eight-hour day as well as a living wage.

The British Empire Steel Corporation (Besco) was controlled by President Roy M. Wolvin and Vice-President J.E. McLurg who defended these conditions by frankly stating “Coal must be produced cheaper in Cape Breton, poor market conditions and increasing competition make this an absolute necessity. If the miners require more work, then the United Mine Workers of America District 26 Executive must recommend acceptance of a 20% wage reduction.” The stage had been set for a sequence of events that would lead to the tragic death of a union brother and father of 10 children, William Davis.

In the early days of 1925, J.E. McClurg added insult to injury by eliminating credit for miners at the company store and further reducing days of work at the collieries. On March 6, 1925, UMWA strategist, JS McLachlan, left with few options, called for the removal of all maintenance men from the collieries; a 100% strike was necessary to do battle with Besco. If the company would not negotiate an end to this deprivation and hunger, the mines would slowly fill with floodwater and die. The company response was brief and derogatory, “We hold the cards, they will crawl back to work, they can’t stand the gaff.”

The next two months were filled with grief and hardship; Besco cut off the sale of coal to miners houses and mounted a vigorous public relations campaign to blame the miners for their own predicament. The UMWA lobbied for intervention from the Liberal Provincial and Federal governments to no avail; this prompted the union’s most difficult decision to date. On June 3, 1925, the UMWA withdrew the last maintenance men from Besco’s power plant at Waterford Lake. In retaliation, the company cut off electricity and water to the Town of New Waterford, which included the hospital filled with extremely sick children. For more than a week the town mayor, P.G. Muise, literally begged company officials to restore electricity and water to his townspeople. Besco ignored his requests.

On June 11, 1925, drunken company police charged down Plummer Avenue on horseback, beating all who stood in their path. They rode through the schoolyards, knocking down innocent children while joking that the miners were at home hiding under their beds. It was the last straw.

At 10 am in New Waterford, the UMWA was organizing an army of angry miners. They were determined to restore electricity and water to their homes and families; they marched on the Waterford Lake power plant and were met by a wall of armed company thugs on horseback. Before the miners could state their demands, the riders charged the front line firing wildly into the crowd. Gilbert Watson was shot in the stomach – he carried the bullet until the day he died in 1958. Michael O’Handley was shot and trampled by horses. William Davis, an active member of the UMWA was fatally shot through heart by a British Empire Steel Company thug.

The miners’ reaction was swift and decisive. They swarmed the power plant, overpowered the company police and marched them off to the town jail. For several nights afterward, the coal towns were under a state of siege by the miners. They raided the company stores to feed their starving families and then burned the stores to the ground to eliminate the last symbol of corporate greed and servitude in the Cape Breton coalfields. The company stores never re-opened after the coal wars of 1925.

The miners promised that no man would ever again work the black seam on Davis Day. They kept that promise ever since. In coal mining communities, many storeowners close shop in respect for deceased coal miners and local schools close to commemorate Davis Day.

The history of mine workers is filled with memories of class struggle and of brotherhood. It is summed up in the words of former District 26 President Stephen J. Drake – “There is no finer person on this planet than the working man who carries his lunch can deep into the bowels of the earth. Far beneath the ocean he works the black seam an endless ribbon of steel his only link to fresh air and blue skies. The steel rails symbolize a miners’ life, half buried underground, half reaching toward his final reward. William Davis epitomized a miners’ life – it was filled with simple pleasures, family, friends and sunshine. He will always be one of us, he will never be forgotten.”